1. Introduction

If you’ve ever seen a black box out of curiosity, you might’ve thought it’s just another piece of aircraft hardware. But for me, after 10 years covering aviation, every time I see one I feel a lump in my throat—not because of its tech, but because of its story.

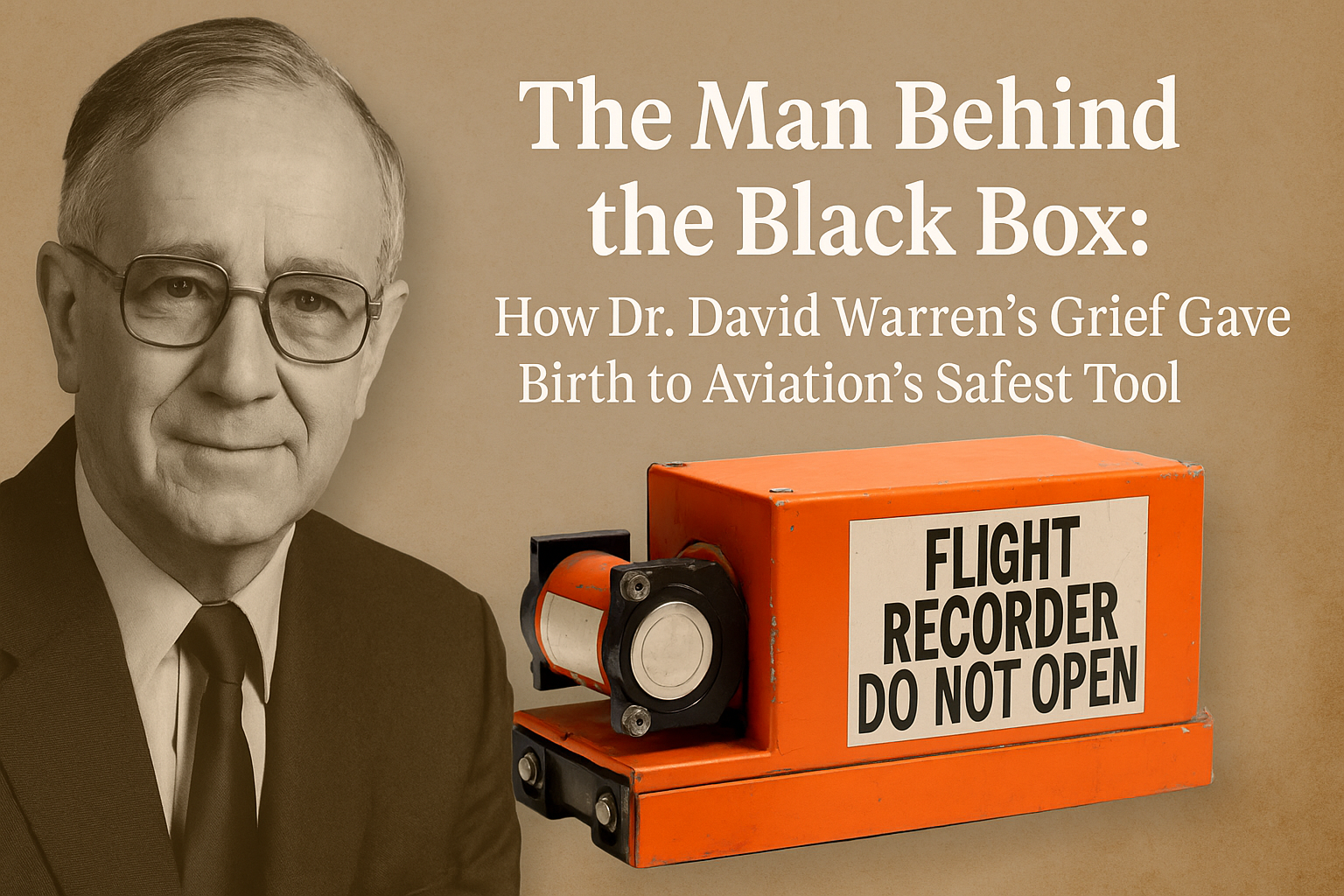

That story begins in 1934, with a boy named David Warren. The plane carrying his dad vanished over Bass Strait — no wreckage, no explanations. That silence became his compass. Later, as a chemist and engineer, he built a device that would speak when everything else was quiet. What he created was the flight data recorder (FDR) — not just a tool, but a guardian. It was born from grief but designed to save.

The “black box flight recorder” was never just about wires and memory; it was about remembrance and truth. And over the years, it has become one of the most powerful instruments in aviation safety, especially in missions of black box recovery, when answers are buried beneath tragedy.

This blog is a tribute to how personal heartbreak became a global safeguard.

2. A Boy Shaped by Mystery

Picture a 12-year-old by the water’s edge, watching day turn into a dark pool of unanswered questions. Little David didn’t fly jets. He didn’t study aerodynamics. But he felt loss so acutely that he dedicated his life to ending that void.

Growing up, David trained himself to notice patterns—the way clouds moved, how sound bounced. That curiosity, I believe, was also his healing mechanism. He became a chemist, then an aviation researcher. His search for closure became a search for solutions.

3. When Modern Jets Became Ghost Stories

By the 1950s, jet travel transformed the world; people were crossing continents in hours, not days. And yet Comet aircraft kept crashing mysteriously. Each time, wreckage was found, but no “why.” Media and engineers were baffled.

When I talk to veterans who worked those investigations, they remember it like a dark cloud moving over the field—one crash after another, and the same refrain: We just don’t know.

That haunting lack of reason led Warren to ask: Could we record what was happening—on the plane and in the cockpit—before everything went wrong?

4. Building the First “Memory Box”

In 1958, Warren rigged together recording equipment and flight sensors into a prototype. It was clunky—tape reels, cartridge players, early memory devices—but it worked. He called it a Flight Memory Unit.

He invited colleagues to a demo. The machine whirred. His voice echoed in the room. But the audience was skeptical: “Who listens to pilots’ chatter?” “What about costs?” “Isn’t this intrusive?”

He responded calmly, but firmly: “It’s not about blame. It’s about truth.” That phrase became his mantra.

5. Rejection, Persistence, and Overseas Allies

At home, the idea of cockpit monitoring faced legal and cultural resistance—pilots feared liability, companies feared regulation. He was essentially ignored.

Warren didn’t give up. He approached institutions in Britain, then Canada and the U.S. Eventually they listened. Soon experimental flights carried these recorders. Airlines started to see value: no longer would crashes end in mystified reports—they’d have real answers.

Then, after another crash near Australia, domestic authorities realized that Warren’s box could save future investigations. In 1967, Australia instituted mandatory flight recorder rules. Nearly 40 years after 1934, David Warren’s path from tragedy to triumph came full circle.

6. What the Box Catches: Heartbeat and Humanity

Here’s how it works — mind, imagine riding shotgun on a flight:

Flight Data Recorder (FDR): It archs through mechanical data—speed, altitude, engine thrust, pitch—like a plane’s heartbeat. It stores up to 25 hours of perfect flight.

Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR): This one preserves pilot conversation, cockpit noise, occasional silence. Up to two hours of sound — the words, the tone, the pauses, even the hush. A phrase as subtle as “Oh, no…” can unlock an entire narrative. The data details “what,” the voice reveals “how we felt.”

In effect, every flight is a short story. And in crisis, it’s a lifeline.

7. Why Orange? A Beacon in Chaos

People assume black boxes are black. Not. They’re painted international orange—loud, vibrant, impossible to miss. That color was no aesthetic choice—it was lifesaving.

Crash scenes are chaotic: ocean swells, forest floors, snow, fire-blackened metal. Amid it all, that orange screams: Find me. I know what happened.

It’s a humble stroke of design genius. In a field obsessed with aerodynamics, Warren recognized something tactile: survivors need sight. Investigators need speed. That box needs to be the first thing they see.

8. Moments Where the Box Gave Meaning

• Air France 447 (2009)

Sank silently into the Atlantic. Black boxes found two years later at 4,000 meters. They revealed instrument failure and pilot confusion—crucial for safety reforms.

• Germanwings 9525 (2015)

Incredibly tragic. A co-pilot, locked out and alone, flew a plane into a mountain. CVR confirmed it. The findings led to new cockpit protocols worldwide.

• Boeing 737 MAX Crashes (2018–19)

The black box exposed software bugs that now shape how the industry scrutinizes automation.

Each time it spoke, it reshaped policy, restored trust, saved lives.

9. Emotion Behind the Investigation

Talking to investigators, I’m always struck by how they brush data off as “just numbers.” But their eyes say the truth—they stay when they listen to that last cockpit minute. And they tell me, “It never gets easy.”

They’ve choked up hearing pilots say, “I love you, honey…” or “We’ve got a problem.” That emotional chord is their burden—and their duty. They say it’s not just a record. It’s a memory keeper.

10. Warren’s Quiet Legacy

David Warren didn’t live for accolades. He became a Commander of the Order of Australia in 2001, but shunned the spotlight. He always said he just wanted others to stop asking “Why?”

Because of him:

- Crashes are solved faster

- Pilots are trained more realistically

- Families receive closure

- Engineers revise designs faster

He changed aviation with empathy encoded in metal.

11. What Comes Next—And What Remains

Today, we use streaming flight data, longer-life beacons, encrypted memory chips. Some forecast the end of the black box’s era.

But I don’t buy it—not yet. That box is reliable, tactile, and carries meaning. No streaming data has ever comforted a grieving family the same way that battered orange box rising from the deep can.

12. Conclusion

Dr. David Warren turned a childhood tragedy into one of aviation’s greatest acts of service. He didn’t just invent a box—he gave aviation a conscience, a memory, and a voice.

Every time we fly, that silent recorder—tucked modestly in the tail—stands ready not just to record numbers, but to preserve our stories, honor the lost, and guide improvements for the living. Whether it’s an everyday flight or the aftermath of disaster, the plane crash black box remains the most trusted witness — carrying voices, data, and dignity through fire, water, and time.

It’s as if Warren said, “You can’t steal your father’s voice… but perhaps I can help you hear the next one.” I think he succeeded.

FAQ 1: Why is it called a black box if it’s orange?

It’s a contradiction that surprises many. The term “black box” actually comes from early engineering slang—a mysterious device that holds secrets inside. But in aviation, visibility can mean survival. So the recorder is painted bright international orange, not for style, but so search crews can spot it quickly amid ocean waves or wreckage. The name stuck, but the color is a beacon.

FAQ 2:What made Dr. David Warren’s invention so meaningful beyond the technical side?

To understand that, you have to start with the boy — not the scientist. Dr. Warren lost his father in a plane crash where no one ever found out why. That silence shaped him. His invention wasn’t just about data; it was about making sure no family would ever have to live with endless, unanswered questions again. What he created was part machine, part memorial. He didn’t build a recorder. He built a promise — that the next voice wouldn’t be lost in silence.

FAQ 3: Can families of crash victims access what’s inside the black box?

Not directly. The audio from the cockpit is treated with enormous respect. Only trained investigators—often from national safety boards—are allowed to hear it. Transcripts may be included in final reports, but actual recordings are rarely, if ever, released. It’s an emotional line between transparency and dignity. Families are given findings, closure, and context—but never a tape that could reopen wounds.

FAQ 4: Has a black box ever failed during a major investigation?

Very rarely—and that’s a testament to how incredibly tough they are. Built to survive explosions, deep-sea pressure, and thousand-degree heat, they’re engineered not just for data storage but for survival. In extreme cases like MH370, where the black box remains unfound, it’s not failure of the device but the vastness of the environment that prevents recovery. Still, each incident pushes improvements in black box recovery tech and tracking methods.

FAQ 5: What made Dr. David Warren’s invention so revolutionary?

He wasn’t just solving an engineering puzzle. Warren was healing a human wound—his own. After losing his father in a crash that left no clues, he envisioned a device that could speak after silence. His invention gave aviation not just a memory system, but a moral compass. It changed how we investigate, learn, and grieve. Every time that orange box is found, Warren’s legacy whispers: “We remember. We will do better.”